MERRY MEADOWS - Chapter 9 - Analyzing the Disconnect

While making our millions before we turned thirty was a

popular benchmark amongst friends that I also subscribed to, I was never

seriously fired by the desire for big bucks and lavish life styles. It was

quite the contrary in fact. Maybe it required the kind of guts and effort that

I was too lazy to work up, or too scared to contemplate. Slowly I drifted out

of my inherited circle of friends. These were all well-heeled scions of the

super privileged classes, and driven by their singular pursuit of inherited businesses

and lifestyles.

Civil Servants all over the world suffer from this dilemma.

While in service they are courted by the capitalist class, especially in

government regulated economies like Pakistan’s. All manner of favour seeking

takes place in the search for competitive advantage, and block tackle with a

partial referee blowing the whistle in your favour is the name of the game.

For Civil Servants of weak spirit the flesh is often enticed

by the lure of riches proffered by the favour seekers, and such bureaucrats are

well set with bulging coffers as and when retirement rolls around, and they

make the transition from civil servant to capitalist, hobnobbing with ease with

the financial and social elite who would once line up outside their offices.

Even while in office such bureaucrats live the highlife,

with evenings spent in the lap of luxury ensured by the favour seekers. When

the odd kick in the gallop becomes the norm, and the template is warped beyond

repair, then it becomes well neigh impossible for the God fearing to align with

the system, and they either get out, or are kicked out. In the case of my

father and two uncles they were kicked out, casualties of a war that cost us

half the country.

The few civil servants with noble spirit and strong flesh,

and they used to be in a majority at one point, do not have a problem in the

transition, no matter how abrupt or traumatic. They have lived their

lives as Spartan warriors and dispensed justice without fear or favour. In so

doing these upright and honest officers invariably develop authentic authority

which is value driven and timeless, and does not diminish post-retirement.

Provided the Spartan in the warrior doesn’t have a change in heart and become

desirous of the opulent lifestyle of the capitalist.

That was never the conscious desire, the opulent lifestyle

of the capitalist, when I chose self-employment as my career. That is what my

father had done when he ‘retired’ from the Indian Provincial Civil Service and

migrated to Pakistan. And since I had consciously chosen not to be a part of

the Civil Service of Pakistan for reasons explained earlier, self-employment

was the route to take, following in my father’s footsteps as it were, but as a

primary career and not as a post-retirement time filler.

To gain a fuller appreciation about why I’m making such a big deal about my gainful employment, or the lack thereof, as a freelance writer one would need to travel back in time with me, and join me in the reliving of my personal story; of being born into a privileged Indian Muslim family that ‘fled’ to Pakistan 19 years after Partition, in 1966; of my lonely preteen years, spent floundering academically, being one of two Muslims in a class of thirty in Nainital, the much celebrated Indian hill station where I found very little to celebrate; of my early teens, spent in utter misery away from home in Aitchison, learning from scratch the Urdu language, and enduring barely the rough and tumble of a boarding school existence;

Of my late teens, spent adjusting to coeducational surroundings and the many distractions that come with freedom in college, while coping with the death of my father; of my early twenties, filled with squash, debates, girls, jam sessions and discotheques, and a love-hate relationship with mathematics in the undergrad years in which hate triumphed yielding a less than satisfactory academic score, putting it mildly; of my mid to late twenties, living the heady life of a successful entrepreneur running a chain of Taekwondo schools, and spending money like there was no tomorrow, something I lived to regret; of age 28, pretty much the high point of my life in retrospect, representing Pakistan in Sweden as chef-de-mission and winning the 1981 world team squash championships; and then the beginning of my trial and tribulation in right earnest with my thirtieth birthday.

If I were to pick a particular year for when life got

uncomfortably serious it would have to be 1983. It was when realization dawned

with the force of a sledge hammer that sent me reeling.

Up until then I had lived a relatively carefree life. I must

have been pretty thick skinned, or perhaps self-preservation had sent me into

denial, for what I had experienced in my twenties should really have brought on

the realization a whole lot earlier.

The breakup of Pakistan in 1971; the identity crisis that

afflicted every Pakistani, more so us university students; the systematic

dismemberment of the civil service that followed, effectively removing it as a

career option for me, a career that had been my uncles’ and father’s, one they

had prided in; the deaths of my father and uncles, broken and disillusioned; my

titular rise to head of a deeply fractured joint family; the breakup of the

joint family; leaving the joint family house and starting life in a new abode;

marriage; children.

I should have seen it coming as early as 1980, one full year

before I rose to the high point

of my life. In 1980 I got married, and spent my honeymoon visiting my elder

sister in Jeddah. The fact that the trip was financed from proceeds obtained

from the sale of my younger sister’s car, a silver grey Mazda808, should have

sent alarm bells ringing, but they didn’t, perhaps because it wasn’t really a

honeymoon that we were going on.

I had acquired a manpower recruiting license, a prized

possession and theoretically the key that would unlock an untold treasure.

Needless to say, my brother-in-law was very well connected politically, and my

license was amongst the first thirty to be issued.

While the license in itself would not lay any gold eggs, the

fact that my brother-in-law was posted in Jeddah as head of intelligence, and

interacting with Saudi royalty and bureaucracy on a daily basis, held much

promise for the future. Acquiring employment visas for Saudi Arabia would be no problem.

So, in that context, selling my younger sister’s car was a

very good business investment, and in as far as the honeymoon was concerned,

well, we would do it in style once the gold eggs started rolling in.

But they never did, not in the manner that I had expected,

anyway. My wife and I spent weeks in

Jeddah performing multiple Umras, and visiting the holy sites in Medina. All

through that period I couldn’t bring myself to broach the subject of my

business with my brother-in-law. I just couldn’t.

Then, with less than a week to go for the Hajj, and the

opportunity to perform it with the royal Saudi entourage thanks to my

brother-in-law, my wife and I were overcome with this sense of urgency to

return to Pakistan, and we did. I was back in Karachi , and flat broke.

My engagement with the Pakistan Squash Federation in the

conduct of the Pakistan Open had been the 'silly' reason for that sense of

urgency to return. Not performing Hajj that year, gifted to me and my wife on a

platter as it were, would appear to most as a major self denial of divine

blessing.

But in retrospect it wasn’t. My prosperity at the time was

predicated on future earnings that had yet to materialize. As matters stood I

had sold my younger sister’s car to pursue a business trip. The intention to

perform Hajj had never been there, and so it was not to be.

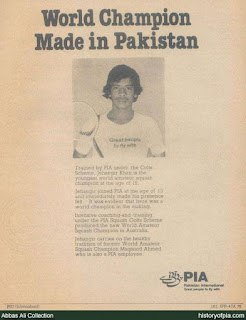

The Pakistan Open that year in 1980 raised the curtain on

Jahangir Khan, and my efforts in organizing the Karachi Squash Association and

the Sindh Squash Association earned me the gratitude of the Pakistan Squash

Federation that manifested itself in my appointment as manager, coach and

chef-de-mission of the Pakistan squash team to the world championship in

Sweden.It was a rare honour indeed, for the Pakistan team comprised Jahangir

Khan, world ranked number one, Qamar Zaman, world ranked number two, Maqsood

Ahmed, world ranked number four, and Daulat Khan, world ranked number seven.

Winning the world team squash title was a foregone conclusion.

Spending six weeks in that beautiful country Sweden , leading

a team that comprised of the world number one, two, four and seven, we were

treated like visiting royalty every step of the way. My wife and I finally had

our honeymoon, one year later, but in a fashion that money could just not have

bought.

The 1981 Pakistan Squash Team that won the World Team Championships in Sweden. Left-to-Right: Qamar Zaman, Daulat Khan, myself, Maqsood Ahmed, and Jahangir Khan, reclining on the bonnet of the Volvo rented for the trip.

The 1981 Pakistan Squash Team that won the World Team Championships in Sweden. Left-to-Right: Qamar Zaman, Daulat Khan, myself, Maqsood Ahmed, and Jahangir Khan, reclining on the bonnet of the Volvo rented for the trip.

She was there when King Carl Gustav presented us with the

trophy. She was the toast of the victory celebrations in the Egyptian team

manager’s suite where the champagne bottles popped, only because under Zia’s

rule celebrating in this manner, with champagne and caviar, in the Pakistan

chef-de-mission’s penthouse suite would not have been kosher. Jahangir Khan,

Qamar Zaman, Maqsood Ahmed, and Daulat Khan were like family, ferrying back to

Pakistan the crystal gifts and purchases made by my wife all over Sweden, in

particular Gavle.

Those were very heady days, and the missed Hajj, and my

broke status back home, were pushed back into the deep and dark recesses of our

minds. All that mattered was the green blazer that bore the Pakistan squash colour,

and the jovial company of the four best players in the world, all attired the

same way, with ‘Bhabi’ ruling the roost.

Returning to Pakistan

from Sweden was in many ways

not as bad as returning to Pakistan

from Jeddah the previous year. The common factor was the cash crunch. But that

now appeared in the shape of a minor irritant that would soon vanish.

For all intents and purposes I had made a successful

transition from taekwondo entrepreneur to squash entrepreneur. There were

squash courts to build, squash players to train and promote, and squash events

to organize. My future most definitely lay in sports marketing and management.

Mark McCormack was my role model and Jahangir Khan my first asset under formal

contract for three years.

There is, however, many a slip between the cup and the lip.

Professional sports in Pakistan ,

I learnt through hard experience, are the sole preserve of the bureaucracy, and

when it comes to world champions there could be no room for an upstart like me.

Suffice it to say that from the dizzy heights achieved in Sweden

I plunged to dismal depths engineered by a vicious bureaucrat in the sports

ministry who, wielding the power of government largess, had my contract with

Jahangir cancelled, challenging me to go to court if I dared, which I didn’t. I

did, however, manage to make a tidy amount selling squash courts, before the

bureaucracy caught up with me and put me out of business, forcing me back to

the planning board, a place where I have spent much of my life.

Why I didn’t get into bed with the bureaucracy and milk the

‘holy cow’ of the State of Pakistan, like every successful 'entrepreneur' was

doing, is a question that continues to bedevil my family and friends to this

day. I admit that I too was agitated by my inability to pay a bribe. I brought

up this issue of not being able to pay a bribe in a dinner get together

organized by Bhai Saeed for old classmates from the IBA.

Our Marketing professor Dr. A. G. Saeed was there and still

going strong. I asked him that of all the courses taught by the IBA, not one

prepared us for this all pervasive ground reality in the conduct of business.

The extent to which the government intrudes in the business domain is certainly

no state secret. I never once came across the concept of ‘speed money’ during

my time at the IBA.

Despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, I have

consciously maintained a high level of respect, bordering on holding sacred,

the representatives of the state, of which I consider myself as one by virtue

of my national squash colour. Add to this my belief in merit and the pursuit of

excellence, and the giving of full measure.

Therefore, for me to pay a bribe to get done that which

should have been done in the first place has never been an option. The coercive

presence of the state is so all pervasive in the world of business that

recourse to ‘speed money’ is pretty much the norm, especially for newcomers who

lack the size and clout to get things done on merit.

To family and friends who knew me then it might appear that

I keep exaggerating my financial plight. My wife had inherited a substantial

asset base of her own, and from my own inheritance I owned the roof that we

lived under.

It was my own efforts at generating an income that had of

late yielded dismal results, and the monies made as a taekwondo entrepreneur

had long gone. Living off the fat of the land, as it were, didn’t suit me at

all, and it suited my wife even less. That added to my misery.

At the theoretical level all my bases were fully loaded.

There was no dearth of access to people in the corridors of power, and in a

patronage driven economy like Pakistan ,

I was all set to becoming the next multimillionaire, if not billionaire, and

power broker. Millions meant much in those days.

But my induction into the patronage game had been quite

‘inauspicious’, a complete disaster in fact, given my inability to make that

one request to my brother-in-law, a request that he would most certainly have

complied with, in retrospect, had I but asked. Many years later I would hear

Bob Urichuck say, ‘if you don’t ask, you don’t get.’ One thing is for certain.

The Lord most definitely works in mysterious ways, and if you don’t ask and

don’t get there and then, then it’s for a reason that is far more beneficial in

every way than instant gratification.

My genetic inability to play the patronage game that

entailed an often shameless embrace of sycophancy, had been further fortified

one year later by the Swedish experience. I had now been blessed with the Pakistan colour, and in a field of endeavour

where Pakistan

held complete sway over the world. The Lord had rewarded me most richly for

pushing the right buttons on the Saudi visas and Hajj issues. It was a reward,

however, that further isolated me from my peers who were adept at operating in

the gray areas of life. It made me far more rigid than ever before when it came

to making requests and accepting favours that affected my livelihood but

required of me to play second fiddle to people clearly bent on plundering the

public’s trust.

My wife, in the mean time, was driven to distraction. It is

the fate of most wives married to men driven by a sense of higher purpose. She

found me stubborn and unreasonable in my pursuit of self-employment when

clearly I was doomed to fail in it, given my disposition and the business

culture I found myself in.

She couldn’t understand then, and I doubt whether she has

figured it out yet, as to why I wouldn’t complete my MBA and seek employment in

some multinational, and rid us once and for all of this gloom cast by my

self-inflicted financial insecurity in the name of noble poverty?

She couldn’t fathom the realization that had dawned on me in

slow stages, acquiring the force of a sledge hammer that had me reeling. There

was no way out for me. Taking refuge in a cushy employment shelter with my head

firmly in the sand was not an option. That was not why my father had left his

pension and retirement plans in India

when he moved to Pakistan

in 1966, a year before his retirement. The 1965 war had made up his mind.

My father was seized with a higher purpose when he finally

opted for Pakistan .

He came here to make a difference, and denied himself untold riches by walking

the straight and narrow. My father left his entire life’s work in India . The

priceless goodwill that he had built in his many postings as a provincial

services officer in Uttar Pradesh, and the last few years of his tenure as

deputy collector and district magistrate for Naini Tal, was left behind for

good, never to be of any use to him or his family, in particular me.

My father had spent his life having people pleading their

cases before him, demanding and getting justice from him. My father was an

honest, upright, fearless, and God fearing Muslim officer in increasingly Hindu

India. He had dispensed even handed justice amongst Muslims, Hindus, Christians

and members of all other faiths on the merit of their cases, and in the process

earned their undying gratitude.

No matter how hindu India got, it would not have made

an iota’s difference to my father. Right through life he had backed his

positional authority with mint authentic authority steeped in righteous

conduct. I was supposed to inherit that undying gratitude of the countless

people whose life he had touched. That was a priceless fortune that I was

denied as a consequence of his decision to move to Pakistan .

Once in Pakistan

he, true to form, turned his back on the easier and cushier options that his

own brothers-in-law showered upon him. They were amongst Ayub Khan’s proud and

privileged, and need I say more.

Instead, my father entered his retirement life learning the

trade of a trader and embracing self-employment, pounding the pavements of

Karachi when he should have been relaxing in the cool climes of Nainital, the

hometown of that great white hunter Jim Corbett, showing tourists around the

fabled jungles of Kumaon deep within which my father had set up court in a

tent, taking justice to the people.

My father and I never discussed a great deal, but that never

stopped me from adopting him as a role model. There was plenty to draw from the

examples that he set. On the drive to Delhi from Nainital to catch the PIA

Super Constellation to Karachi there was one remark of his that I distinctly

remember, and it was a remark that he made a number of times as if trying to

convince himself of it. “We have burnt our boats.” It left me a bit confused at

the age of fourteen, but in retrospect I now understand what he meant. Our

assets in India ,

both tangible and intangible, were now in our past and unavailable, and our

future would be built on that which was as yet unknown.

As it turned out, my father’s future was a big anticlimax.

The vision of Pakistan that Indian Muslims had at the time, that of a ‘pak

sarzameen’, a land pure as the driven snow that was powered exclusively by a

higher purpose, was rudely and brutally broken. His turning his back on

government jobs and contracts, his refusal to ensconce himself in ivory towers,

brought him face to face with ground realities that shocked and broke him. The

myth of Muslim unity at the grassroots functional level, and the prevalence of

parochialism, provincialism, sectarianism and racialism that culminated in the

emergence of Bangladesh just

four years after his move to Pakistan ,

was more than he could bear, and he passed away from his mortal confines on

Chaand Raat in 1972. I was nineteen years of age at the time.

Comments

Post a Comment