JAHANGIR KHAN REVISITED

By Adil Ahmad

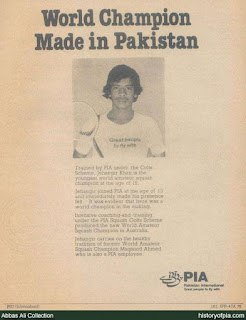

(former chairman Karachi Squash Association,

and chef-de-mission and manager of the

1981 Pakistan Squash Team – Jahangir Khan, Qamar Zaman, Maqsood Ahmed and

Daulat Khan – that won the World Team Championships in Stockholm (Sweden) beating Australia

in the final).

Few men have raised the profile of their country in the

world the way that Jahangir has. He is perhaps the only good remembrance that

we have from the Zia-ul-Haq era, and even there many would disagree. What good

was it conquering the world of a squishy black rubber ball when the country

itself was going broke? But skeptics aside, the emergence of Jahangir on the

world stage threw Pakistan

a lifeline at a time when the Pakistani people were tottering on the verge of

terminal depression. A popularly elected leader had been strung up in

unceremonious fashion by jackboots that had managed to lose half the country

not so long ago. In a way Jahangir embodied the indomitable spirit of the

Pakistani people, specially the noble and warlike Pathans who were taking the

battle to the Soviets in Afghanistan .

Wherever in the world Jahangir went he received far more than the accolade

reserved for a world champion.

During his career Jahangir won the World Open six times and

the British Open

a record ten times. Between 1981 and 1986 he was unbeaten in competitive play

for five years. During that time he won 555 matches consecutively. This was not

only the longest winning

streak in squash history, but also one of the longest unbeaten runs

by any athlete in top-level professional sports. Jahangir retired as a player

in 1993, and then went on to serve as President of the World Squash

Federation between 2002 and 2008.

Today Jahangir spends his time monitoring his many investments

worldwide which in Pakistan

include a textile unit and sports complex. The recession has dried up

sponsorships for the sports complex which is under construction at the site of

the fabled PIA Squash Complex on Karachi ’s

Kashmir Road

that PIA, under the fallible wisdom of its past chairman Air Marshal Daudpota,

renamed the Jahangir Khan Squash Complex in acknowledgement of his many

conquests. Subsequently PIA gifted Jahangir the property to do with what he

pleased.

There are many who feel, and rightly so, that PIA should

have laid the foundations of a brand new squash complex to honour Jahangir’s

achievement. The PIA Squash Complex held historical importance as the world’s

first purpose built squash facility, constructed under the personal supervision

of the legendary Air Marshal Nur Khan who would often visit the site in the

middle of the night to ensure that the contractors were on their toes.

Having

said that, if there was anyone who had earned the stripes to tamper with squash

history, it was Jahangir Khan. Had he decided to demolish the facility and

shift upon the site his textile unit, I am sure the world would have accepted

his decision, and applauded him for it, for at least in the eyes of the squash

playing world Jahangir can do no wrong.

Born on December 10th,

1963 in Karachi, Jehangir Khan is considered by many to

be the greatest player in the history of the game. He is the worthy recipient

of the Hilal-e-Imtiaz (Crescent of

Excellence), the second highest honor given by the Government of

Pakistan to both the military

and civilians. It is awarded

for distinguished merit in the fields of literature, arts, sports, medicine, or science for civilians.

Jahangir was coached initially by his father, Roshan Khan, the 1957

British Open champion, but more out of paternal love than any real hope of

Jahangir making the grade since Jahangir had a medical condition that doctors

said would not permit the stress and strain of a professional squash player’s

career. But a couple of hernia operations later the family was hard pressed to

keep Jahangir away from the squash courts.

In 1979 the Pakistani selectors did not consider Jahangir for

the team that would play in the world championships in Australia, judging him too

physically weak. But there were those who had seen the young lad train under

cousin Rahmat, and knew differently. Jahangir was privately entered in the

World Amateur Individual Championship and, at the age of 15, became the

youngest-ever winner of that event, making squash officialdom eat crow, an

acquired taste that it has developed a substantial appetite for over the years.

In November 1979 tragedy struck and Jahangir's older brother

Torsam Khan, one of the

leading players on the international squash circuit in the 1970s, died unexpectedly

of a heart attack

during a tournament match in Australia .

Torsam's death affected Jahangir profoundly, and some say that it provided him

with the emotional impetus that propelled him into the realms of the extraordinary.

He considered quitting the game, but decided to pursue a career in the sport as

a tribute to his brother.

In 1981, when he was 17, Jahangir became the youngest winner

of the World Open, beating Australia 's

Geoff Hunt, the game's dominant

player in the late1970s, in the final. 7/9, 9/1, 9/2, 9/2. It was an epic,

energy sapping final that physically and emotionally devastated a man on the

brink of being hailed as the greatest squash player the world had ever known,

on the verge of relegating Hashim Khan to number two. Geoff Hunt, however, had

managed to pull off a victory against Jahangir in the final of the British Open

that year, 9-2, 9-7, 5-9, 9-7. But the effort involved was too great and

heralded the end of an incredible Aussie era.

That tournament marked the start of an unbeaten run which

lasted for five years. The hallmark of Jahangir’s play was his incredible

fitness and stamina, which he owed in great measure to the punishing training

and conditioning regime put in place by Rehmat Khan. Jahangir was by far the

fittest player in the game, and would wage a battle of attrition, wearing his

opponents down through long rallies played at a furious pace.

The “Who’s Who”

of world squash fell at his feet, demolished by a force too powerful to resist.

Geoff Hunt, Dean Williams, Chris Dittmar, Qamar Zaman, Ross Norman, and Jansher

Khan were his opponents in the six World Opens that he won in 1981, ’82, ’83,

’84, ’85, and ’88. None of these matches went to five games, often

characterized by an embarrassing one-sidedness. In 1986, ’91, and ’93 Jahangir

made the World Open final, but went down to Ross Norman (9-5, 9-7, 7-9, 9-1),

Rodney Martin (14-17, 15-9, 15-4, 15-13), and Jansher Khan (14-15, 15-9, 15-5,

15-5) in encounters that were vicious but poetry in motion nevertheless.

His ten British Open wins came against Hiddy Jehan (1982),

Gamal Awad (1983), Qamar Zaman (1984), Chris Dittmar (1985), Ross Norman (1986),

Jansher Khan (1987), Rodney Martin (who met him thrice in 1988, ’89, and ’90),

and Jansher Khan (1991). Of these ten title wins, the score-line suggests that

the Aussie Rodney Martin proved his most combative opponent, taking him to five

games in 1989 (9-2, 3-9, 9-5, 0-9, 9-2). The year before that, in 1988, Rodney

had taken Jahangir to four games (9-2, 9-10, 9-0, 9-1). In his last British

Open win in 1991 Jansher took him to four games as well 2-9, 9-4, 9-4, 9-0. All

the others were straight sets that ended in embarrassingly short durations. The

only time he was a runner-up in the British Open was in 1981 when he lost to

Geoff Hunt in four games 9-2, 9-7, 5-9, 9-7.

Jahangir’s unbeaten run of five years and eight months, and

555 matches, finally came to end in the final of the World Open in 1986 in Toulouse, France, when Jahangir went

down to New Zealand's

Ross Norman. The squash

grapevine was abuzz with all manner of speculation. Some said that Jahangir had

sprained an ankle while playing the Malaysian Open, and his playing the World

Open soon after was a tactical error on the part of his managers. But there

were more ominous rumours afoot.

Jahangir’s complete sway over the game was

driving sponsors away by making the outcome so predictable. He had been under

pressure to loosen his grip. Jahangir’s own response was pretty matter of fact.

"It wasn't my plan to create such a record,” he said. “All I did was put

in the effort to win every match I played and it went on for weeks, months and

years. The pressure began to mount as I kept winning every time and people were

anxious to see if I could be beaten. In that World Open final, Ross got me. I

was unbeaten for another nine months after that defeat."

With his dominance over the international squash game in the

first half of the 1980s secure, Jahangir decided to test his ability on the

North American hardball

squash circuit in 1983, making the hike across the Pond until 1986.

Jahangir played in 13 top-level hardball tournaments during this period,

winning 12 of them. He faced the leading American player on the circuit at the

time, Mark Talbott,

on 11 occasions, all in tournament finals, and won 10 of their encounters.

With his domination of both the softball and hardball

versions of the game, Jahangir truly cemented his reputation as the world's

greatest squash player. At the end of 1986 another Pakistani squash player, Jansher Khan, hailing from

the same village

of Nuakilli

Jahangir ended Jansher's winning streak in March 1988, and

went on to win 11 of their next 15 encounters. The pair met in the 1988 World

Open final, with Jahangir emerging the victor. The two JKs would continue to

dominate the game for the rest of the decade. Jansher and Jahangir met a total

of 37 times in tournament play. Jansher won 19 matches, and Jahangir 18

matches. Jahangir did not win the World Open again after 1988, but he continued

a stranglehold over the British Open title.

The secret to Jahangir’s success lay in his superlative

mental and physical prowess. Jahangir revealed that he never had any fixed

training regime particularly designed for him, nor had he any specially

formulated diet. He would eat anything hygienic but, never miss his two glasses

of milk every day. For his training, he would often start his day with a 9 mile

jog which he would complete at a moderate pace, followed by short bursts of

timed sprints.

Later he would weight train in the gym, and finally cool down in

the swimming pool. This routine he would follow five days a week. On the 6th

day he would match practice, and rest on the 7th day. Jahangir would run on

every surface, from custom-built tracks to asphalt roads, grassy farm fields and

seashores in ankle high sand and knee deep waters. High altitude training under

low oxygen conditions was an integral part of his physical conditioning

conducted in the upper reaches of the Karakorum

mountain range in Pakistan .

All in all it made Jahangir one of the most physically and mentally fit

athletes in the world.

Jahangir retired as a player in 1993 after helping Pakistan win

the World Team

Championship in Karachi .

The Government of Pakistan honored Jahangir with the awards of Pride of

Performance and Hilal-e-Imtiaz,

as well as the title of Sportsman of the Millennium. Time Magazine has named

Jahangir as one of Asia 's Heroes in the last 60

years. He was conferred with a Honorary Doctorate of Philosophy by London

Metropolitan University for his contributions to the sport. Jahangir

is listed in the Guinness Book

of World Records as having the most world championship squash

titles.

In 1990, Jahangir was elected Chairman of the Professional

Squash Association, and in 1997, Vice-President of the Pakistan Squash

Federation. He was elected as Vice-President of the World Squash Federation in

November 1998, and in October 2002 was elected WSF President. In 2004, he was

again unanimously re-elected as President of the World Squash Federation at the

International Federation's 33rd Annual General Meeting in Casa Noyale , Mauritius.

There are many who feel that Jahangir could have been better

utilized in his post retirement period, and that the Government of Pakistan has

not leveraged the phenomenal goodwill that he, and others of his ilk who

populated the sports department of PIA, had accumulated during the course of

their incredible careers. “They should have been formally accredited as

Pakistan’s roving ambassadors showing the country’s flag in the four corners of

the world, something they were well accustomed to doing,” says a human resource

development analyst, who laments the manner in which Jahangir, Jansher, Zaheer

Abbas and others were summarily dismissed from PIA. “Instead, they were belittled

and cast aside, and left to their own devices. Had Jahangir been retrained to

function as a formal diplomat, and posted to the United Nations perhaps, with a

strong and competent team, we could have long resolved the problems of Kashmir and Palestine .

Instead, Jahangir was allowed to waste his time at the World Squash Federation

lobbying for the inclusion of squash in the Olympic movement, a pipe dream that

will never come true.”

Jahangir currently lives in Karachi , with his wife, Rubina, and their two

children, Omar and Marium. In his book ‘In the Line

of Fire: A Memoir’ the former president of Pakistan Pervez Musharraf makes a

telling comparison. "If Hollywood only knew his story of tragedy, grit and

determination it would make another movie like Chariots of Fire.

Many of those who know him consider him the best athlete who ever lived."

The question is, why would the West make a movie that extols the exploits of

the East?

Great writeup

ReplyDeleteJAHANGIR KHAN REVISITED" captures the essence of resilience, discipline, and unmatched excellence qualities that parallel the reliability and performance of top-tier energy solutions. Just as Jahangir Khan dominated the squash world with unparalleled consistency, premium energy storage products like tubular batteries excel in durability and efficiency. If you're looking for reliable energy solutions, JDIYAN International has a variety of options for you. Check out our high-quality collection and buy tubular batteries designed for optimal performance and longevity. Whether for industrial use or household energy needs, our batteries stand out as the best choice for those who value reliability and power.

ReplyDelete